Guide to Using SharePoint as Your Department Information Hub

In today’s dynamic workplace, scattered docs and siloed knowledge are kryptonite to company success. But fear not, collaboration champions! SharePoint, the hidden gem within the Microsoft 365 realm, is here to swoop in and save the day. This guide isn’t just about manuals and menus; it’s your roadmap to transforming SharePoint into a vibrant information hub that empowers your team to conquer any project.

Imagine this:

- One-stop shop for everything: Ditch the endless email threads and file hunts. Create a central repository for policies, procedures, project documents, even team photos – all accessible with a single click.

- Knowledge power: Unmask your department’s hidden experts. Build wikis, Q&A forums, and knowledge bases, fostering information sharing and turning everyone into a resource.

- Goodbye, communication chaos: Break down silo walls with team site features like announcements, news feeds, and chat channels. Keep everyone in the loop, on the same page, and singing in key.

- Tailored workflows, seamless collaboration: Forget clunky processes and lost approvals. Design custom workflows for document revisions, task management, and approvals, keeping projects moving like greased lightning.

- Personalization for the win: Give everyone a stake in the hub. Customize dashboards, news feeds, and views to suit individual needs and preferences. No two colleagues, no two identical information experiences.

This isn’t just about organization; it’s about igniting the power of your team. By breaking down information barriers and fostering open communication, you’re creating a dynamic hub where ideas spark, knowledge flows, and collaboration soars.

Ready to roll up your sleeves and build your dream information hub? This guide will walk you through the entire process, from setting up your site to customizing features, managing access, and keeping everything sparkling clean. You’ll be a SharePoint pro in no time, guiding your department to collaborative nirvana.

Remember, a well-oiled information hub isn’t just a tech feat; it’s a cultural shift. So grab your team, dive into this guide, and watch as your department transforms from scattered islands to a collaborative powerhouse. Information at your fingertips, success within reach – let’s build something amazing together!

Step 1: Set Up Your SharePoint Site

- Access SharePoint:

- Navigate to SharePoint within your Microsoft 365 account. Click on “Create Site” and choose the Team site template, providing a collaborative environment for your department.

- Name and Customize:

- Give your site a meaningful name that reflects your department. Customize the site’s appearance, navigation, and permissions according to your department’s preferences and needs.

Step 2: Structure Your Content

- Create Document Libraries:

- Organize your files by creating document libraries for different types of documents—whether it’s policies, procedures, or project files. This ensures a structured and easily navigable repository.

- Use Metadata and Tags:

- Enhance searchability by utilizing metadata and tags. Classify documents with relevant attributes, making it easier for users to find what they need quickly.

Step 3: Foster Collaboration

- Add Communication Tools:

- Integrate Microsoft Teams, discussion boards, and announcements to facilitate communication. This ensures that important updates, discussions, and announcements are readily available within the SharePoint hub.

- Enable Co-Authoring:

- Leverage SharePoint’s co-authoring capabilities to allow multiple team members to collaborate on documents simultaneously. This enhances real-time collaboration on projects and reports.

Step 4: Customize Your Hub

- Create Custom Lists:

- Use custom lists for tracking tasks, events, or any other department-specific information. Tailor these lists to meet the unique needs and workflows of your department.

- Implement Workflows:

- Automate processes with SharePoint workflows. Whether it’s approval processes, document review, or task assignments, workflows can streamline routine tasks and enhance productivity.

Step 5: Enhance Accessibility and Security

- Set Permissions:

- Define user permissions to ensure that sensitive information is accessible only to those who need it. SharePoint’s robust permission settings allow you to control access at various levels.

- Enable Mobile Access:

- Make your information hub accessible on the go by enabling mobile access. SharePoint’s responsive design ensures a seamless experience across devices.

Step 6: Train Your Team

- Training Resources:

- Provide training resources to your team, ensuring they are familiar with SharePoint’s features. Microsoft offers a wealth of tutorials and guides to help users navigate and utilize the platform effectively.

- Regular Updates:

- Keep your team informed about updates and improvements to the SharePoint hub. Regularly communicate best practices and encourage feedback to continuously optimize the platform for your department’s needs.

Step 7: Monitor and Iterate

- Analytics and Usage Reports:

- Use SharePoint’s analytics and usage reports to monitor the performance of your information hub. Analyze user engagement, popular content, and areas for improvement.

- Gather Feedback:

- Actively seek feedback from your team. Regularly gather insights on the usability and effectiveness of the information hub, making adjustments based on user suggestions and evolving departmental needs.

By following the information shared in this guide, you can embark on a journey with SharePoint, elevating it into a resilient and sophisticated information hub. This dynamic evolution extends beyond merely centralizing your department’s resources; it encompasses an enhancement of collaboration, communication, and overall productivity.

One of the key facets of this transformation lies in SharePoint’s extensive customization options. Tailor the platform to your department’s unique needs, creating an environment that aligns seamlessly with your workflows and objectives. Whether it’s structuring document libraries, implementing custom lists, or automating processes with intuitive workflows, the customization capabilities empower you to mold SharePoint according to the distinctive requirements of your department.

Furthermore, the seamless integration that SharePoint offers with other Microsoft 365 applications amplifies its impact. As part of the Microsoft ecosystem, SharePoint synergizes effortlessly with tools like Teams, Outlook, and OneDrive. This interconnectedness fosters a cohesive digital workplace, where information flows seamlessly between applications, ensuring that your team operates with maximum efficiency and synergy.

Navigating through SharePoint’s user-friendly interface becomes a journey of exploration rather than a task. The intuitive design ensures that your team can effortlessly engage with the platform, promoting widespread adoption. This accessibility, coupled with features like co-authoring capabilities and mobile access, translates into a collaborative environment where information is not only centralized but is also easily accessible and actively utilized by every team member.

In essence, SharePoint emerges not just as a repository of resources but as a powerful catalyst for fostering a collaborative and well-informed departmental environment. It transforms into a dynamic space where information is not static but is constantly evolving to meet the needs of your team. As your department navigates the complexities of modern work dynamics, this transformed SharePoint stands as a beacon, enhancing the collective capabilities of your team and propelling productivity to new heights.

According to Section 112.1 of 40 CFR, the requirement for a Spill Prevention, Control and Countermeasure Plan (SPCC), applies to petroleum storage facilities that:

According to Section 112.1 of 40 CFR, the requirement for a Spill Prevention, Control and Countermeasure Plan (SPCC), applies to petroleum storage facilities that:

On December 29, 1970, President Nixon signed the

On December 29, 1970, President Nixon signed the

If you have never had a serious accident in your company headquarters or meeting place, count yourself lucky. In the United States, we live in a litigious society, and if someone is injured while away from home, that injured person may very well file a lawsuit against the company owning or running a building or piece of equipment. Even meeting or event organizers can be at risk. Insurance companies and courts look kindlier on organizations that have a written safety plan. Having a plan in place shows you have considered potential safety hazards, and are doing your best to follow all regulations, educate all participants, and thus prevent an accident.

If you have never had a serious accident in your company headquarters or meeting place, count yourself lucky. In the United States, we live in a litigious society, and if someone is injured while away from home, that injured person may very well file a lawsuit against the company owning or running a building or piece of equipment. Even meeting or event organizers can be at risk. Insurance companies and courts look kindlier on organizations that have a written safety plan. Having a plan in place shows you have considered potential safety hazards, and are doing your best to follow all regulations, educate all participants, and thus prevent an accident.

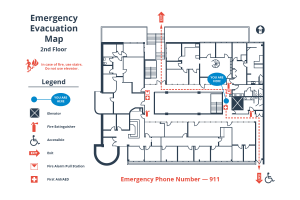

Normally, a workplace must have at least two exit routes to permit prompt evacuation of employees and other building occupants during an emergency. More than two exits are required if the number of employees, size of the building, or arrangement of the workplace will not allow employees to evacuate safely. Exit routes must be located as far away from each other as practical in case one exit is blocked by fire or smoke.

Normally, a workplace must have at least two exit routes to permit prompt evacuation of employees and other building occupants during an emergency. More than two exits are required if the number of employees, size of the building, or arrangement of the workplace will not allow employees to evacuate safely. Exit routes must be located as far away from each other as practical in case one exit is blocked by fire or smoke.